On July 30, 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump abruptly announced a 25% tariff on all goods from India, effective August 1, 2025, coupled with an unspecified “penalty” targeting India’s purchases of energy and military hardware from Russia. This move – framed by Trump as a response to a “massive” U.S. trade deficit with India and India’s “vast” imports from Russia– marks a sharp escalation in U.S.-India trade tensions. It underscores the increasingly complex interplay between economic policy and geopolitical strategy in international affairs.

This development did not occur in isolation. Since early 2025, the Trump administration has wielded tariffs as leverage over several trading partners. In April 2025, a 26% reciprocal tariff on India was threatened (dubbed the “Liberation Day” tariffs), though implementation was paused amid negotiations. The newly imposed 25% tariff essentially revives that earlier plan at a slightly reduced rate, catching New Delhi off guard which had anticipated a lower figure around 15–17% based on U.S. deals with other countries. Together with the vague Russia-related penalty, these measures elevate pressure on India, reflecting U.S. willingness to use economic tools to pursue broader strategic aims.

This article below analyzes the reasons behind the U.S. tariff decision, the landscape of India-U.S. trade, sectoral impacts on India, comparative tariff disparities, legal and diplomatic considerations, and the responses from the Indian government and industry. It also explores how these tariffs epitomize the intersection of trade and geopolitics, and what it means for India’s strategic autonomy in navigating great power dynamics.

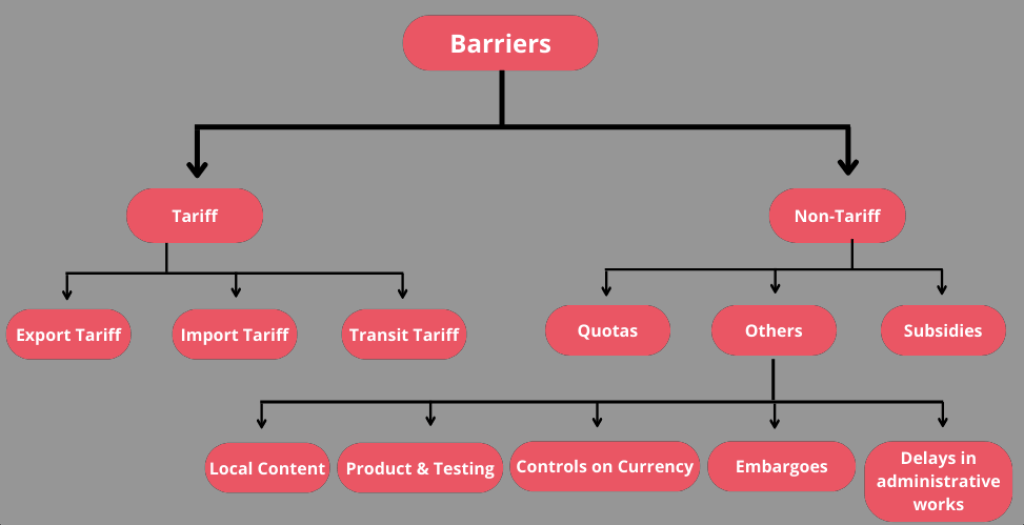

What are tariffs?

Tariffs are a kind of trade barrier that raises the price of goods brought in from other countries compared to goods made in the US. Usually, tariffs are taxes or levies that importers have to pay, and these costs are passed on to customers. As a way to safeguard their own businesses, countries often utilise them in international trade.

For instance, in February 2025, President Trump put a 25% tax on goods coming into the US from Canada and Mexico and a 10% tax on goods coming in from China. There is also a 10% tax on Canadian energy resources.

Why Are Tariffs and Trade Barriers Used?

Protecting Jobs at Home: Imported goods could make things harder for domestic industries by making them more competitive. To save money, these corporations may fire workers or move production to other countries. This will lead to more unemployment and a less pleased electorate. When people talk about unemployment, they often bring up how cheap foreign labour is and how bad working conditions and a lack of rules let foreign corporations make items for less. But in economics, countries will keep making things until they lose their comparative advantage (which is not the same as an absolute advantage).

Keeping Customers Safe A government can put a tax on goods that it thinks could be dangerous to its people. For instance, a country might put a tax on beef that comes from another country if it feels the meat could be infected with a disease.

New and emerging industries: Many emerging countries adopt the Import Substitution Industrialisation (ISI) strategy to defend their new sectors with tariffs. In industries where it wants to encourage growth, the government of a developing economy will charge tariffs on goods that come from other countries. This raises the prices of items that come from other countries and makes a market for goods made in the US. It also protects those businesses from being pushed out by lower prices. It lowers the number of people who are out of work and lets emerging countries move from growing crops to making things. People who don’t like this kind of protectionist stance say that it costs too much to help new sectors get started. If an industry grows without competition, it might make lower-quality items, and the government might have to give it money to keep it going, which could slow down economic progress.

Security of the Nation Developed countries also use barriers to preserve some industries that are seen as strategically significant, such those that help keep the country safe. People frequently think that defence businesses are very important to the government and give them a lot of protection. For instance, both Western Europe and the United States have a lot of factories, but they are both quite protective of enterprises that make things for the military.

Retaliation: If a country thinks that a trading partner hasn’t followed the rules, it may also use tariffs as a way to get back at them. For instance, if France thinks that the US has let its wine makers call their sparkling wines “Champagne” (a designation that only applies to the Champagne region of France) for too long, it can put a duty on goods that come into the country from the US. France will probably quit retaliating if the U.S. agrees to stop the wrong labelling. If a trading partner goes against the government’s goals for foreign policy, retaliation can also be used.

Common Types of Tariffs

There are several types of tariffs and barriers that a government can employ:

- Specific tariffs

- Ad valorem tariffs

- Licenses

- Import quotas

- Voluntary export restraints

- Local content requirements

- Specific Tariffs

Reasons Behind the U.S. Tariff Imposition

President Trump’s announcement on his Truth Social platform was unambiguous in citing multiple justifications for the tariff on India. The key reasons include:

- Trade Deficit Concerns: The U.S. goods trade deficit with India reached $45.7 billion in 2024, a 5.4% increase from 2023. Trump views this imbalance – where U.S. imports from India far exceed exports – as evidence of an unfair trading relationship. He described the deficit as “massive” and emblematic of how India has “done very little business” with the U.S. on equitable terms. Reducing bilateral deficits has been a consistent goal of Trump’s trade policy, and India’s surplus is a clear target.

- India’s Tariffs and Non-Tariff Barriers: The Trump administration criticizes India’s own import barriers, arguing that India maintains high tariffs and restrictive regulations that hinder U.S. exports. Trump has called India’s non-monetary barriers – such as certain sanitary/phytosanitary rules and subsidies – among the most “strenuous and obnoxious” in the world. For example, stringent agricultural import standards and subsidies supporting Indian farmers are viewed in Washington as protectionist measures that limit market access for U.S. products. The tariff threat is thus partly retaliatory, pushing India to lower its trade barriers in a future deal.

- BRICS and De-dollarization India’s active role in BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa) has added friction. Washington perceives BRICS initiatives – such as promoting trade in local currencies or exploring a new reserve currency – as challenges to U.S. dollar hegemony. President Trump even warned in February 2025 that BRICS nations could face “100% tariffs” if they undermine the role of the U.S. dollar. India’s participation in discussions on alternatives to the dollar within BRICS (e.g. a potential common currency or non-dollar payment systems) has raised concern in the U.S. that New Delhi may be aligning with efforts deemed “anti-American”. The new tariff can be seen as a signal dissuading India from moving too far with BRICS on monetary alternatives. (Notably, BRICS members publicly rejected the “anti-American” label; Brazil’s President Lula defiantly stated, “The world has changed. We don’t want an emperor,” in response to Trump’s threats.

- India-Russia Defense and Energy Ties: A significant wrinkle in this tariff announcement is the unspecified “penalty” for India’s purchases from Russia. Trump explicitly linked India’s “vast majority” sourcing of military equipment and its status as one of Russia’s largest energy buyers to the need for punitive action. The U.S. is increasingly frustrated with India’s continued imports of Russian oil and arms amid the Ukraine war. In fact, Washington is considering extreme measures: a proposed Sanctioning Russia Act of 2025 in Congress would authorize up to 500% tariffs on countries buying Russian oil, gas, or uranium– a staggering penalty that underscores U.S. resolve to squeeze Russia’s trade partners. While this bill is not yet law, its spirit is reflected in Trump’s tariff-plus-penalty approach toward India. The mere uncertainty of what the extra penalty on India might entail (higher duties on certain goods? financial sanctions?) is likely intentional, designed to maximize U.S. leverage in pressing New Delhi to scale back ties with Moscow.

It’s worth noting India’s perspective here. New Delhi has reduced its dependence on Russian arms over the years (Russia’s share of India’s defense imports fell from 72% in 2010–14 to about 36% in 2024) and has diversified to suppliers like France, Israel, and the U.S. Moreover, India has not made any big-ticket Russian weapon purchase in recent years (the last major deal was the S-400 air defense system in 2018). India also insists its oil imports from Russia are guided by energy security and pricing, not support for the war. Nevertheless, India’s refusal to join Western sanctions on Russia, its purchase of discounted Russian crude, and its continued engagement with Russia (e.g. in forums like BRICS) underlie Trump’s decision to impose an extra penalty. In U.S. eyes, these actions undermine the pressure campaign against Moscow and thus warrant a tough response.

In sum, the tariff announcement is driven by a mix of economic grievances and geopolitical calculations. It signals U.S. dissatisfaction with trade imbalances and market access issues, while also tying trade to strategic alignment – implicitly asking India to distance itself from Russia and perhaps from BRICS initiatives, in exchange for better trade terms.

India-U.S. Trade Landscape and Significance

The United States is India’s largest trading partner, making this tariff highly consequential for India’s economy. Bilateral goods and services trade reached about $131.8 billion in 2024-25, and the two nations had set an ambitious goal to more than double this to $500 billion by 2030. In fact, during a cordial summit in February 2025, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Trump agreed to work toward a multi-sector Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) by fall 2025 as a step toward that $500 billion goal. Both leaders spoke of a “fair, balanced, and mutually beneficial” trade pact that would require new terms to unlock the next level of trade cooperation.

Key features of the India-U.S. trade relationship include:

- India’s Exports to the U.S.: India exported roughly $87 billion worth of goods to the U.S. in 2024-25. These exports span diverse sectors – from electronics and engineering goods to pharmaceuticals, textiles, gems and jewelry, and agricultural products. The U.S. alone accounts for about 17% of India’s total exports, underscoring the market’s importance. Notably, India had recently made significant gains in high-tech manufacturing exports to the U.S. (discussed further below).

- U.S. Exports to India: U.S. goods exports to India stood at roughly $41 billion in 2024 (by difference, given the $129.2 billion goods trade and $45.7 billion deficit). Major U.S. exports include crude oil, electronic components, aircraft, machinery, and agricultural goods. India’s large population and growing middle class represent an attractive market, but U.S. firms have often cited tariff and regulatory barriers in India as obstacles (for example, high duties on electronics or price controls in medical devices).

- The Persistent U.S. Trade Deficit: As noted, the U.S. had a goods trade deficit of $45.7 billion with India in 2024, up from about $43 billion in 2023. India enjoys a surplus largely due to its competitive exports in sectors like pharmaceuticals, IT services, and jewelry. While the U.S. runs services trade surpluses with India (thanks to education, travel, and financial services), the goods deficit has been a political sticking point. U.S. officials argue this reflects market distortions (e.g. India’s import tariffs average around 15% for many products, higher than U.S. tariffs) and want more reciprocal access.

- Recent Negotiations: Prior to the tariff bombshell, India and the U.S. were deep in talks to resolve trade irritants and perhaps clinch a “mini trade deal” or BTA. Multiple rounds in New Delhi and Washington had tried to bridge gaps on issues like agriculture and dairy access (the U.S. wants India to open its dairy market and reduce farm subsidies) and digital trade/data storage rules (the U.S. seeks more liberal e-commerce and data flow policies). India, for its part, has been defensive about protecting farmers (it restricts dairy imports to guard its rural livelihoods) and digital sovereignty (seeking local data storage, which U.S. tech firms resist). By mid-2025, these sticking points remained unresolved, and the tariff threat appears to be an attempt to force concessions by creating urgency. Trump’s August 1 deadline for deals – part of his sweeping global tariff strategy – left India with little time, as talks had not yielded a breakthrough.

Importantly, the tariff strikes at a time when India is trying to maintain a delicate balance: deepening strategic ties with the U.S. (in the Indo-Pacific security domain, technology, etc.) while preserving its own strategic autonomy (which includes relations with Russia and participation in groupings like BRICS). The tariff shock thus puts New Delhi in an uncomfortable spot, where economic interdependence with the U.S. collides with independent foreign policy choices.

Key Indian Export Sectors Affected

The across-the-board 25% U.S. tariff threatens to impact virtually all Indian exports to America, but some sectors stand out for their volume and vulnerability. India’s export profile to the U.S. features both traditional industries (apparel, gems) and newer areas (electronics, pharma). Below are key sectors and the tariff’s potential impact on each:

- Electronics and Technology: In a dramatic shift, India became the largest exporter of iPhones to the U.S. in Q2 2025, accounting for 44% of U.S. iPhone imports that quarter. Apple’s “Make in India” expansion saw India overtake China (whose share of U.S. iPhone imports fell to 25% from 61% a year prior). This was a landmark achievement for India’s electronics manufacturing drive. Apple and its suppliers ramped up assembly in India, with plans to increase iPhone production capacity from ~40 million units to 60 million units annually. A 25% tariff directly endangers this success story. Smartphones assembled in India suddenly become 25% more expensive for U.S. consumers, unless Apple absorbs the cost. Industry officials warn that if tariffs persist, India could “lose the electronics manufacturing business for the U.S.” as companies like Apple and Samsung might divert production to other countries or focus on non-U.S. markets. Indeed, Samsung – which had just started exporting India-made phones to the U.S. – indicated it can shift production to its large facilities in Vietnam (which faces a lower U.S. tariff rate of ~20%) to remain competitive. The electronics sector, a bright spot in India’s export diversification, thus faces a serious setback. (Notably, the U.S. has exempted certain Chinese high-tech exports from the highest tariff rates – e.g. some Chinese smartphone exports face ~20% – putting India at an artificial disadvantage if its rate is 25%.) The implication is that without relief, global supply chains could adjust away from India, undermining the country’s bid to become an electronics export hub.

- Pharmaceuticals: India is often called the “pharmacy of the world,” and the U.S. generic drug market is arguably where this is most evident. Indian firms supply roughly 40–65% of all generic medicines used in the U.S., dominating segments of antibiotics, painkillers, and other essential generics In value terms, the U.S. accounts for about one-third of India’s pharma exports (nearly $9 billion in FY2024). Many Indian generics are 50–90% cheaper than branded equivalents, saving American patients and healthcare systems tens of billions annually (cheaper generics saved the U.S. about $408 billion in 2022 alone). Imposing tariffs on these drugs threatens to raise U.S. healthcare costs and create drug shortages, since Indian companies operate on thin margins (often 10–15%). Analysts cautioned that a 25% tariff, if not passed on to U.S. consumers, could render many Indian generic exports “unviable,” possibly forcing companies to withdraw products. This could lead to severe shortages in the U.S. market. Indian pharma industry groups have been lobbying for exemptions, arguing that unlike other goods, medicine is a strategic import for U.S. health security. So far, the tariff technically applies to pharmaceuticals (it’s an across-the-board measure), but it remains to be seen if the U.S. grants carve-outs in practice. Any prolonged tariff on pharma would hurt India’s $13 billion pharma export industry and disrupt global drug supply chains. On the flip side, it could also backfire on the U.S. by driving up drug prices – a classic example of how interdependent economies suffer mutual pain in trade wars.

- Gems and Jewelry: The United States is the largest market for India’s gems and jewelry, especially polished diamonds, gold jewelry, and costume jewelry. In 2024, over $10 billion of Indian gems and jewelry were exported to the U.S., about 30% of India’s global trade in this sector. A 25% tariff directly hits this high-value export category. Margins in the diamond cutting and jewelry business are slim, and Indian products will become significantly more expensive for American importers and consumers. The Gem and Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC) in India voiced deep concern, noting that such a tariff “will place immense pressure on every part of the value chain” and undermine decades of market development in the U.S.. Competing countries like Thailand or Belgium (for diamonds) and Turkey or Italy (for jewelry) could seize market share if they are subject to lower or no such tariffs. Indian exporters may need to find alternative markets for luxury goods or face an inventory glut. The broader implication is a loss of jobs in India’s gems sector (which employs millions, especially in Gujarat’s diamond hubs). This also hurts U.S. jewelry retailers who rely on Indian supply – demonstrating again how these tariffs cut both ways.

- Textiles and Apparel: The Indian textile and garment industry is one of the country’s largest employers and export earners, and the U.S. is a top destination (around 27–30% of India’s textile/apparel exports). With tariffs jumping to 25%, Indian apparel is at risk of becoming uncompetitive in the price-sensitive U.S. retail market. Early signs are worrying: several U.S. buyers have reportedly advised Indian textile exporters to halt shipments – even for confirmed orders – until there is clarity or a resolution. The sudden 25% cost increase could lead to order cancellations as American importers turn to suppliers from countries like Bangladesh (which enjoys tariff-free or lower-tariff access for garments) or Vietnam. An apparel industry representative cautioned that Indian products would become 7–10% more expensive than some competitors’ even with the tariff disparities that already existed. That margin can decide whether a retailer switches sourcing. There are also reports that exporters in India’s textile hubs (like Tiruppur for knitwear) fear “mass layoffs” if U.S. orders dry up. Given that India exported about $8 billion in textiles and clothing to the U.S. last year, the stake is huge. If half of that faces trouble, entire regional economies could suffer. The timing is unfortunate too – the tariff hit comes just after India signed an FTA with the UK (offering hope of export growth there) and while negotiating one with the EU. The U.S. action thus threatens to nullify gains from other trade deals and divert orders to competitors.

- Others: Virtually every sector – leather footwear, furniture, chemicals, auto parts, agricultural products like seafood or rice – is impacted by the blanket tariff. For instance, India is a major supplier of shrimp and seafood to the U.S., but now faces 25% duty while countries like Ecuador face 15%. Indian marine product exporters worry that customers will shift to Ecuador or Vietnam for seafood imports, though some note that capacity can’t shift overnight and buyers might hold off until negotiations conclude. Similarly, Indian handicrafts and furniture exporters fear losing market share to Southeast Asian rivals. Auto parts (an area where India was expanding exports) become pricier for U.S. manufacturers who import them. Even IT services could feel indirect heat – while services aren’t tariffed, strained relations might influence U.S. firms’ outsourcing decisions if the dispute escalates.

In aggregate, about $85–87 billion of India’s goods exports to the U.S. would be subject to this 25% tariff. Estimates suggest if fully applied, the tariffs could shave off around 0.5% from India’s GDP growth due to export losses and knock-on effects However, much depends on the duration of the tariffs – whether this is a short-lived negotiating tactic or a longer trade rupture. Indian officials and businesses are hoping for the former (a temporary pain until a deal is struck), but preparing contingency plans in case of the latter.

Comparative Disadvantage: India vs. Others

One of India’s biggest concerns is that it has been singled out for harsher treatment compared to other countries negotiating trade terms with the Trump administration. Throughout 2025, the U.S. has been striking bilateral tariff deals worldwide, leveraging Trump’s threat of global tariffs. By August 1, the U.S. had announced agreements with numerous partners – creating a patchwork of differentiated tariff rates. In this landscape, India’s 25% stands out as one of the highest new tariffs among major economies. For context:

- Japan and the European Union (EU) – both close U.S. allies – reached deals that kept their tariffs to 15% on exports to the U.S. These were part of Trump’s push for “reciprocal” tariffs under negotiated quotas. A 15% rate, while higher than zero, is far more manageable than 25% and suggests significant concessions were made. (Japan, for instance, reportedly offered large reciprocal investments in the U.S. and purchases of American goods to secure a lower tariff.)

- South Korea – another ally – similarly got a 15% rate, likely also by agreeing to some U.S. demands (Seoul had renegotiated the KORUS FTA back in 2018 and perhaps built on that foundation).

- Indonesia and the Philippines – emerging Asian partners – saw tariffs around 19–20% after making deals. Notably, Pakistan, which was initially lumped in the 25% tier with India, managed to secure a trade deal lowering its U.S. tariff rate to 19% just days before the deadline. In a dramatic move, Trump announced a deal with Pakistan to jointly develop its oil reserves, pointedly commenting “Who knows, maybe they’ll be selling oil to India some day!”. This was a clear geopolitical signal alongside a tariff concession – rewarding Pakistan and hinting at it supplanting Russia as an energy supplier to India in the future.

- Vietnam – a direct competitor to India in textiles and electronics – was reportedly pegged at 20% tariff. Vietnam’s large existing exports of furniture, apparel, and phones to the U.S. now have a 5 percentage-point edge over India’s. Bangladesh and Turkey (major apparel rivals) are also in the 15–20% rangeas per early reports.

- China – the biggest trade rival – is a special case. U.S.-China tariffs largely predate this wave (from the 2018–2019 trade war). While Beijing hasn’t signed a new deal under Trump’s 2025 campaign yet, it’s expected to get off easier because of its leverage in critical areas like rare earth minerals (vital for U.S. industry). Negotiations with China were said to be at an advanced stage, potentially yielding a partial easing rather than escalation, since decoupling fully from China is costly for the U.S. supply chain.

What this means for India is a stark competitive disadvantage. Indian goods now face higher U.S. tariffs than those from almost any other major economy. This discrepancy, even if short-term, can cause immediate trade diversion. American importers will favor countries where tariffs (and thus costs) are lower – a phenomenon already being observed in sectors like apparel and electronics. New Delhi fears a loss of market share that could persist even if tariffs are later removed, because once buyers establish alternate supplier relationships, switching back isn’t guaranteed.

Indian officials have openly voiced frustration that India was expecting to be treated on par with friends like Japan or at worst given a rate similar to Vietnam’s, and felt blindsided by the 25% figure. This has political ramifications: it feeds a narrative that India’s strategic overtures to the U.S. (e.g. joining the Quad, deepening defense ties) were not enough to secure economic goodwill when it mattered. Some analysts in India caution that over-reliance on the U.S. market is risky, and this episode might accelerate India’s efforts to diversify export destinations (for instance, capitalizing on the UK trade deal and pushing to conclude an FTA with the EU quickly, or exploring markets in East Asia and Africa).

From Washington’s perspective, the tariff disparities are a deliberate carrot-stick strategy – countries that cooperated on U.S. terms got sweeter deals, while those that held out (or in India’s case, pursued independent policies with Russia/BRICS) got the stick. The U.S. is leveraging its market power to force policy changes among partners, effectively weaponizing supply chains and trading flows for strategic ends. This is a defining feature of the “America First” trade diplomacy under Trump’s second term.

Legal Framework and WTO Considerations

The United States has invoked domestic legal authorities to justify these tariff actions, chiefly citing the Trade Expansion Act Section 232 (national security) and Trade Act Section 301 (unfair trade practices), as well as the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) for broad economic sanctions. In public, President Trump frames the tariffs as necessary for U.S. national security and as a response to unfair practices. For example, steel and aluminum tariffs since 2018 were imposed under Section 232, alleging that reliance on foreign metals threatened U.S. security. Similarly, the administration could claim India’s barriers warrant Section 301 action (the same legal tool used against China’s IP practices in 2018).

However, in the international trading system, these justifications are contentious. World Trade Organization (WTO) rules generally prohibit raising tariffs above bound levels (for the U.S., most tariffs are bound at very low rates) except under specific exceptions. The U.S. is leaning on the national security exception (Article XXI of GATT), which is a self-judged clause allowing measures “necessary for the protection of essential security interests” during war or emergencies. Historically, countries invoked this sparingly, but the Trump administration’s broad use of it (for steel, tech, and now potentially general tariffs) has tested the limits.

WTO panels in late 2022 ruled that the U.S. Section 232 steel/aluminum tariffs violated WTO obligations, rejecting the idea that they were bona fide security measures in a war scenario. The panels (in disputes brought by China, India, EU and others) found that simply invoking “security” doesn’t grant unfettered freedom – there are bounds to its use. The U.S. bluntly disagrees with these rulings, maintaining that national security is not justiciable by the WTO. In practice, the U.S. appealed those panel decisions “into the void,” as the WTO Appellate Body is currently paralyzed (a situation the U.S. itself caused by blocking judge appointments). This means dispute enforcement is stalled – members like India have “won” in principle but cannot get authorization for retaliation via the WTO appeals process, because the appeals are in limbo.

India has been actively challenging U.S. tariffs through the WTO and contemplating its legal options:

- WTO Disputes: India filed disputes against the 2018 steel and aluminum tariffs and recently consulted on newer U.S. measures. As noted, while panels have sided with complainants, the U.S. stance and Appellate Body impasse blunt the impact. India could escalate by joining other countries in a makeshift appeals mechanism (MPIA) excluding the U.S., or by proceeding unilaterally.

- Retaliatory Tariffs: Under WTO norms, if a violation is found, the affected country can impose commensurate retaliatory tariffs. Back in 2019, India prepared a list of retaliatory tariffs (on U.S. agricultural goods like almonds and apples) in response to U.S. metals tariffs, but largely held off pending negotiations. It “reserved its right” to retaliate and even notified the WTO of potential duties. Given the new 25% tariff, India might dust off those plans. Some trade experts suggest India could impose its own tariffs on U.S. imports even without WTO authorization, as a political signal of resistance (the EU, Canada, and China did this in 2018 in limited fashion). However, this carries risks of further escalation and deviates from India’s general compliance with WTO rules.

- Legal Argument – Abuse of Security Exception: India could formally dispute the 25% tariff as a GATT violation, arguing the U.S. is abusing the national security justification. It might cite prior WTO rulings that countries can’t use security as a blanket excuse for protectionism. But pursuing this legally might be more symbolic than effective, due to the lack of an appeal mechanism to enforce any victory.

All this is happening against the backdrop of a weakened multilateral trading system. The WTO’s Appellate Body remains defunct (largely due to U.S. obstruction), so binding dispute resolution is broken. The WTO Ministerial discussions to reform the system are ongoing but slow. In the meantime, trade conflicts are being managed through bilateral bargains or tit-for-tat retaliation, rather than through adjudication. The India-U.S. tariff spat exemplifies this: both sides have referenced WTO rights, but ultimately they are negotiating politically, outside Geneva.

From India’s viewpoint, the WTO’s limitations mean it must rely on diplomacy and coalition-building. India has aligned with others in criticizing U.S. invocation of security for economic measures. There’s an inherent contradiction: the U.S. insists its actions are WTO-legal (security exception), yet its very approach undermines the WTO’s credibility. India, traditionally a supporter of multilateral rules, is now forced to consider unilateral countermeasures or fast-tracked trade deals as workarounds.

India’s Official Response and Strategy

The Indian government’s initial reaction to Trump’s tariff announcement was measured and cautious. The Ministry of Commerce and Industry released a statement noting that it had “taken note” of the U.S. President’s remarks and was studying the implications. Officials emphasized that India and the U.S. have been engaged in ongoing talks to reach a “fair, balanced, and mutually beneficial” agreement, and India remains committed to this process despite the setback.

Key elements of India’s official stance include:

- Emphasis on Diplomacy: New Delhi underscored that channels of communication remain open. The government refrained from any combative rhetoric. Instead, it pointed to the positive trajectory of talks so far and expressed hope that a solution would emerge through dialogue. The External Affairs Ministry spokesman, when pressed by media, highlighted that India-U.S. ties have “weathered several transitions and challenges” in the past and that the focus remains on the substantive agenda both sides are committed to. This suggests India does not want this episode to derail the broader strategic partnership (defense, Indo-Pacific cooperation, etc.) and is signaling patience and resolve.

- Protecting Core Interests: At the same time, India’s statement put its red lines front and center – namely, that national interest and the welfare of its citizens will guide any deal. The Commerce Ministry explicitly mentioned the priority of protecting farmers, small businesses (MSMEs), and entrepreneurs in trade negotiations. This mirrors India’s stance in all recent trade talks (e.g., India walked out of RCEP in 2019 on concerns for farmers and industry). By reiterating this, India is telegraphing that while it seeks a compromise, it will not simply capitulate to U.S. demands that hurt its vulnerable sectors. For example, opening agriculture or dairy markets widely to U.S. products could harm Indian farmers – a politically sensitive issue. India is holding firm that any bilateral pact must respect these sensitivities, just as its deal with the UK did.

- Reference to Other Deals: Interestingly, India’s statement referenced the recently concluded Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the United Kingdom (July 2025). By doing so, India signaled two things:

- It is capable of signing major trade agreements when its interests are accommodated,

- It won’t settle for less with the U.S. than it achieved with the UK in terms of balanced outcomes.

- The subtext is that India has options – it can deepen trade with other partners if the U.S. route becomes untenable. It’s also a gentle reminder that India made concessions in the UK deal (for instance, on liquor tariffs, data exchange, etc.) but also secured protections for its sectors; it expects a similar give-and-take with Washington.

- No Immediate Retaliation Announced: Notably, India did not announce any retaliatory tariffs or sanctions of its own in response. This restraint likely reflects a desire to de-escalate and keep negotiations on track. Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal and other officials have indicated that all necessary steps will be taken to safeguard India’s interests, but for now, those steps appear to be diplomatic – seeking U.S. exemptions or reductions – rather than tit-for-tat tariffs. India has, however, kept the option of WTO action and reciprocal measures on the table by saying it will “examine implications” thoroughly.

- Engagement with U.S. Delegation: A U.S. negotiating team is expected to visit India later in August 2025. India’s strategy is to use that opportunity to press for a resolution. New Delhi will likely bring proposals to address some U.S. concerns: perhaps offering to increase imports of American goods (like energy or civilian aircraft), further reduce tariffs in select categories, or update some regulatory standards – but all within limits that don’t politically backfire at home. India might also leverage areas of U.S. interest such as big defense purchases or opening up to U.S. tech investments as bargaining chips.

In essence, India’s official approach is a blend of firmness and conciliation – standing firm on core interests and not reacting impulsively, while conveying openness to continue talks. This calibrated response aims to avoid a breakdown in relations. It also positions India as a responsible player in contrast to Trump’s abrupt tariff move, thereby hoping to garner international understanding and perhaps quiet support.

Industry and Business Reactions in India

Indian industry groups and exporters have responded with dismay and concern to the tariff announcement. Many had not anticipated an outcome this harsh and are now scrambling to assess impacts and contingency plans. Some notable reactions and trends:

- Exporters’ Associations: The Federation of Indian Export Organisations (FIEO) termed the 25% tariff a “major setback for Indian exporters”, particularly in labor-intensive sectors like textiles, footwear, and furniture.

- Textile Hubs: Representatives from Tiruppur Exporters’ Association (a major knitwear exporting cluster) tried to strike a hopeful tone publicly, calling the tariff “just a negotiation tactic” and expressing optimism that a trade agreement will be reached “imminently” to remove it. However, privately, many textile exporters are indeed pausing shipments. There’s a real fear of order cancellations and payment issues for goods in transit.

- Gems & Jewelry Sector: As mentioned, leaders like Kirit Bhansali of GJEPC have been vocal. They highlighted the $10 billion export figure and 30% dependence on the U.S. market, warning of pressure on the entire chain from miners to artisans.

- Pharma and Healthcare: The pharmaceutical industry’s response has been somewhat calmer, given that medicine is a necessity and there’s hope that practical considerations will lead the U.S. to exempt or quickly reverse tariffs on critical drugs. Indian pharma companies, as Reuters reported in February, believe they can still “retain their dominant market share” even with tariffs, due to lack of alternatives and their cost competitiveness.

- Electronics Manufacturers: Big players like Apple and Samsung are in a wait-and-watch mode but clearly alarmed. An anonymous industry official told media “We are shocked at what President Trump has announced… If maintained, India will lose the electronics manufacturing business for the U.S.” Apple’s suppliers are considering shifting some production or redirecting output to non-U.S. markets. Samsung’s global COO for mobile, Won-Joon Choi, even stated that Samsung had prepared diversification of factories and can shift production locations depending on the final tariff decision. This highlights a risk: global firms using India as a base have the flexibility to move – investment can be footloose. If India’s cost advantage disappears due to tariffs, they’ll relocate production to Vietnam, China (if that becomes viable again), or elsewhere. This is a setback for India’s “Make in India” ambition just when it was yielding results.

In summary, India’s industry is rattled but also rallying to adapt. The immediate reaction is a push for speedy negotiations to remove the tariffs. If that fails, expect a pivot to finding alternate markets (e.g., redirecting exports to Europe, Middle East, etc.), though replacing the U.S. demand in the short run is challenging. The situation has also united various industry lobbies to speak in one voice about the need for a stable and fair trade environment – a message they are sending to both Washington and New Delhi.

Conclusion

The imposition of a 25% U.S. tariff on Indian goods – paired with threats of penalties over India’s Russia ties – represents far more than just a bilateral trade squabble. It epitomizes a new era where economic leverage is deployed as an instrument of geopolitical strategy. In this case, the United States is using access to its vast market as a bargaining chip not only to extract better trade terms but also to influence India’s foreign policy orientation (away from Russia and perhaps to moderate its BRICS stance). This blending of trade policy with strategic goals is a hallmark of the transformed international diplomacy in the 2020s.

For India, this episode is a stern test of its doctrine of “strategic autonomy.” India has long prided itself on maintaining independence in global affairs – engaging all major powers, joining groupings like BRICS and the Quad simultaneously, and refusing to be pigeonholed. Now, it faces punitive measures for pursuing certain ties (with Russia) even as it tries to deepen others (with the U.S.). Navigating this will require deft diplomacy, tactical flexibility, and steadfast focus on national interests.

Some key takeaways and forward-looking points for India include:

- Balancing Economics and Geopolitics: India will need to carefully balance economic interests with strategic partnerships. The U.S. is irreplaceable in certain aspects (technology, defense cooperation, market size), but India cannot completely sever historical ties with Russia overnight without harming its own security and energy needs. Going forward, India might seek to gradually reduce dependence on Russia (a process already underway in defense procurement) to alleviate U.S. pressure, while urging the U.S. to appreciate its energy needs and security concerns in its neighborhood. In essence, India must communicate that it shares many values and interests with the West, but as a developing nation it has its own constraints.

- Trade Negotiation Resolve: The current impasse underscores that India must be ready to drive a hard bargain to protect its economic interests. If a deal is to be struck with the U.S., India will have to negotiate terms that restore preferential tariff rates. This may involve offering concessions like greater access in some sectors or big-ticket purchases. But as India’s response showed, it will insist on safeguarding sectors like agriculture and small industries. The art of the deal will be finding creative solutions – e.g., tariff-rate quotas, phased market openings, mutual standards recognition – that allow both sides to claim victory. India will also seek to institutionalize a dispute resolution mechanism in any BTA so that such tariff shocks aren’t repeated arbitrarily.

- Supply Chain Resilience and Diversification: Indian businesses have learned the hard way that over-reliance on a single market or production base is risky. Just as global firms are now wary of over-reliance on one country (like how companies are China-plus-one diversifying), India too might accelerate efforts to diversify its export markets. Expediting trade agreements with the EU, Canada, Australia, and deepening ties in Asia and Africa could mitigate the impact of U.S. volatility. Domestically, there may be a push to make Indian industry more competitive (lowering costs, improving quality) so that even with some tariffs, they can survive. Government schemes like PLI (Production Linked Incentives) in electronics, or export incentives for textiles, become even more crucial to keep India an attractive sourcing hub despite external headwinds.

- Multilateral and Minilateral Forums: The tariff war also has global implications. It highlights the need for reforming institutions like the WTO to handle security-linked trade measures. India might redouble efforts with the EU, Japan, and others to restore the WTO Appellate Body and update rules, so that countries cannot so easily use national security as a blanket justification. In parallel, forums like the G20 (where India currently holds presidency in 2025) could be used to raise concerns about trade coercion and make the case for fairness and rules-based order. Ironically, India’s position as a leader of the Global South could be bolstered as it stands up to unilateral actions – many developing countries empathize with being caught in great power crossfire. This could drive India to take a more vocal leadership role in shaping new trade norms that prevent abuse of measures like tariffs for political ends.

- Strategic Patience with the U.S.: Despite the turbulence, both New Delhi and Washington know the strategic stakes are high. Over the past 25 years, India-U.S. relations have improved across multiple domains – defense (e.g., foundational military agreements, Quad cooperation), energy, people-to-people ties, and shared concerns about a rising China. These gains are not easily reversible. The tariff fight, if prolonged, could indeed dampen the warmth and prompt India to hedge bets (e.g., reconsidering participation in U.S.-led initiatives). But if resolved, it could also clear the air for a stronger partnership. It is noteworthy that Trump reportedly sought a phone call with PM Modi soon after – likely to negotiate directly. High-level engagement might find a face-saving formula for both sides. Additionally, Trump is slated to visit India later in 2025 (unless the trip is derailed by a lack of agreement). Both governments will want some positive outcome by then. Thus, strategic patience and continued engagement, rather than rupture, seem to be India’s current course.

In conclusion, the 25% tariff saga illustrates how trade diplomacy in 2025 is about far more than tariffs – it’s a theatre where questions of currency dominance, alliance loyalty, and global order are being contested. For a country like India, which aims to emerge as a leading power and a “pole” in a multipolar world by 2047, yielding to pressure on one front could set precedents on others. Therefore, India’s approach is to stand its ground where it must, negotiate where it can, and always keep the long-term relationship in mind. The U.S.-India partnership has immense potential, but this episode shows it requires constant calibration to ensure mutual respect and benefit.

As negotiations continue in the coming weeks, the world will watch closely. A compromise that rolls back tariffs and addresses core concerns would reaffirm the resilience of U.S.-India ties. Failure to reach one could push India to rethink its alignment and spur new coalitions (there’s even talk of reviving a Russia-India-China grouping, though that has its own complications). Ultimately, both democracies have a stake in not just managing this dispute, but in setting a constructive example of how to reconcile economic and strategic interests in an era of great power competition. The hope is that wisdom prevails, producing a solution that strengthens the foundation of one of the 21st century’s most important bilateral relationships – rather than weakening it.