Why in news:

After a prolonged legal battle over sharing Mahanadi river water in a designated tribunal, Odisha and Chhattisgarh have now expressed willingness to resolve the dispute amicably between themselves.

UPSC CSE Relevance:

UPSC CSE in prelims examination has focused on different . A case in point is a following PYQ.

UPSC PYQ 2021:

With reference to the Indus river system, of the following four rivers, three of them pour into one of them which joins the Indus direct. Among the following, which one is such river that joins the Indus direct?

A) Chenab

B) Jhelum

C) Ravi

D) Sutlej

UPSC PYQ 2017:

Q: With reference to river Teesta, consider the following statements :

1. The source of river Teesta is the same as that of Brahmaputra but it flows through Sikkim,

2. River Rangeet originates in Sikkim and it is a tributary of river Teesta.

3. River Teesta flows into Bay of Bengal on the border of India and Bangladesh.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

A) 1 and 3 only

B) 2 only

C) 2 and 3 only

D) 1, 2 and 3

Mahanadi River:

Facts:

- lifeline of Odisha

- originates from the Amarkantak hills in Bastar Plateau of Chhattisgarh.

- It flows for a total length of 851 kilometres, of which 494 km lie within Odisha, before emptying into the Bay of Bengal.

- States in the basin : Chhattisgarh (52.42%), Odisha (47.14%), Maharashtra (0.23%), Madhya Pradesh (0.11%), and Jharkhand (0.1%)

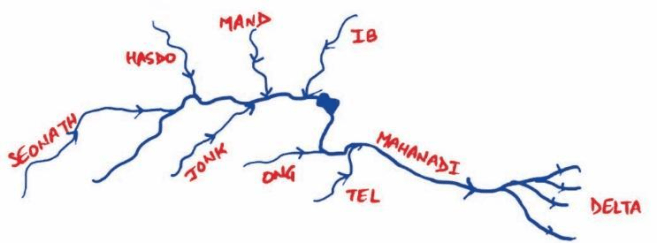

Tributaries:

Left Bank Tributaries:

- Seonath

- Hasdeo

- Mand

- Ib

Right Bank Tributaries:

- Ong

- Tel

- Jonk

The dispute:

- Over time, Odisha observed a considerable decline in the flow of Mahanadi waters entering its territory, attributing this to Chhattisgarh’s extensive upstream construction and increased water usage. Odisha has raised concerns that the reduced river flow has adversely affected irrigation, drinking water supply, and the ecological balance of its sensitive coastal areas.

- In contrast, Chhattisgarh maintains that 52.9% of the Mahanadi’s total catchment area — and 89.9% of the catchment area up to the Hirakud Dam — lies within its borders, giving it the rightful claim to utilise the river’s waters.

- Odisha filed a suit in the Supreme Court on the matter of Mahanadi water dispute. At the final hearing of this suit on January 23, 2018, the top court directed the Centre to constitute a tribunal.

- Accordingly, the Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation constituted the Mahanadi Water Disputes Tribunal (MWDT) on March 12, 2018 under the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956.

Constitutional provisions:

As per VII Schedule

- Entry 56 in Union List includes – Regulation and development of inter-State rivers and river valleys to the extent to which such regulation and development under the control of the Union is declared by Parliament by law to be expedient in the public interest.

- Entry 17 in State List mentions – Water, that is to say, water supplies, irrigation and canals, drainage and embankments, water storage and water power subject to the provisions of entry 56 of List I.

Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956:

- As per above constitutional provisions, Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956 was legislated by Parliament. Major Provisions are :-

- Negotiation and Consultation: The central government is required to first attempt to resolve the dispute through negotiation and consultation among the concerned states.

- Constitution of Tribunal: If negotiations fail, the central government can within a year, by notification, establish a tribunal to resolve the dispute.

- Tribunal Composition: The Tribunal typically consists of a Chairman and other members nominated by the Chief Justice of India from among sitting or retired High Court or Supreme Court judges.

- Adjudication: The Tribunal has the power to investigate the dispute, hear evidence, and make a decision.

- Bar on Supreme Court Jurisdiction: The Act explicitly bars the Supreme Court or any other court from directly entertaining any dispute that falls under the purview of the Tribunal.

- Binding Decision: The decision of the Tribunal is published in the Official Gazette and is binding on the concerned state governments.

- Scheme for Implementation: The central government can formulate a scheme to implement the Tribunal’s decision.

- Bar on Levy of Seigniorage: The Act prohibits states from imposing levies on water use from an interstate river solely based on the location of conservation works within their territory.

- Amendment in 2002: The Act was amended in 2002 to incorporate recommendations of the Sarkaria Commission, including time limits for establishing tribunals and delivering decisions.

Challenges:

- Constitutional Ambiguities: The Constitution places water under the State List (Entry 17) while also giving the Parliament the power to regulate and develop interstate rivers under the Union List (Entry 56). This dual authority creates jurisdictional confusion and makes resolution difficult.

- Loopholes in ISRWD Act 1956 as it does not lay down the principles and standards for resolution of water disputes objectively.

- Ineffective Tribunal System: delayed proceedings with tribunals often taking years, sometimes decades, to deliver their awards.

- For example, the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal, constituted in 1990, gave its final award in 2007, and the matter is still under litigation.

- Lack of Enforcement Mechanism: Tribunal awards are often not strictly enforced. States may defy the decisions, and there is no strong mechanism to ensure compliance.

- Limited Expertise: The tribunals’ composition is often limited to legal experts, lacking a multidisciplinary approach that includes hydrologists, environmental scientists, and other specialists, which is crucial for addressing the technical complexities of water management.

- Post Award Litigations : The Supreme Court continues to entertain litigations on river water disputes over legal questions as well as under Article 21 which encompasses Right to Water within Right to Life further delaying resolution of dispute.

- Politicization of Disputes: Water disputes are frequently exploited by political parties for electoral gains, turning the issue into a matter of regional pride and sentiment. This politicization makes it difficult for states to reach an amicable solution through negotiation.

- Competing Demands: Increasing population, rapid urbanization, and the expansion of agriculture and industry have led to a surge in water demand. This creates intense competition among states for a limited resource.

- For instance, states like Punjab and Haryana, which rely heavily on water-intensive crops like paddy, face acute water shortages.

- Data Opacity: There is a lack of a centralized, transparent, and mutually acceptable water data repository. Without reliable data on river flow, rainfall, and water usage, it is challenging to establish a baseline for fair water allocation, and states often dispute the data presented.

- Changing Rainfall Patterns: Climate change has led to erratic monsoon seasons, resulting in seasonal water shortages in some states and floods in others. This uneven distribution of water intensifies existing disputes.

Way Ahead:

- Establish a Single, Permanent Tribunal: The current ad-hoc tribunal system is a major cause of delays. A single, permanent tribunal with multiple benches, as proposed in the Inter-State River Water Disputes (Amendment) Bill, 2019, would ensure faster resolution with a time-bound process.

- Create a Centralized, Transparent Data Repository: Reliable and universally accepted data on river flows, water usage, and other hydrological information is crucial for fair allocation.

- Enhance the Enforcement Mechanism: A strong enforcement mechanism, possibly overseen by a central authority, is necessary to ensure compliance. The establishment of the Cauvery Water Management Authority (CWMA) to implement the Supreme Court’s verdict on the Cauvery dispute is a step in this direction, though its effectiveness is still being tested.

- Establish a Dispute Resolution Committee (DRC): Creating a negotiation and mediation body, as proposed in the 2019 Bill, to resolve disputes amicably before they escalate to a tribunal could save time and resources.

- Include Technical Experts in Tribunals: To ensure a comprehensive understanding of the technical aspects of water management, tribunals should include not just legal experts but also hydrologists, environmental scientists, and other specialists.